Disclaimer: The work described in this post was done by me and my classmate at IIT-Kanpur, Ankit Goyal. Here is a link to the presentation that we gave.

This is a follow up of my earlier post, in which I explored temporal models, that can be applied to things like part-of-speech tagging, gesture recognition, and any sequential or temporal sources of data in general. In this post, I will describe in more detail the implementation of our project that classified RGBD videos according to the activity being performed in them.

Dataset

Quite a few RGBD datasets are available for human activity detection/classification, and we chose to use the MSR Daily Activity 3D dataset. Since we had limited computational resources (the mathserver of IITK), and a limited time before the submission deadline, we chose to use a subset of the above dataset, and worked with only 6 activities. So, our problem was now reduced to 6-class classification.

Features

In any machine learning problem, your model or learning algorithm is useless without a good set of features. I read a recent paper which had a decent review of the various features used. They were:

- 3D silhouettes - Finding the outline of the human body, and using the shape of this outline as features.

- Skeletal joints or body part tracking - Kinect comes with an algorithm to determine the pose of the body from the depth image alone. Pose here refers to the 3D coordinates of 15 body joints.

- Local Spatio-temporal features - Just like some 2D/3D image feature detector, but with the added dimension of time.

- Local 3D occupancy features - This one seemed the most interesting. What this does is to treat an RGBD video as a function I(x, y, z, t). Now, this a very sparse function, and would be zero at most points in a 4D space. But, whenever a certain activity is performed, certain regions of this 4D space will become filled. Inferring from such data is now a matter sampling it efficiently, and this where all the innovation must lie, if this technique is to work.

- 3D optical flow - The 3D counter part of the popular optical flow, it is also known as [Scene Flow] in the academic literature. This is one paper that makes use of these features.

The features that we ultimately went ahead were the skeletal joints. The MSR Daily Activity 3D dataset already provides the skeletal joint coordinates to us, so all we had to was to take that data, and do some basic pre-processing on it.

Preprocessing the features.

The dataset provides us with the 3D coordinates of 15 human body joints. These cordinates are in the frame of reference of the Kinect. The first operation that we perform on them is the following: to transform the points from the Kinect reference frame to the frame of the person. By frame of the person, we refer to the joint corresponding to the torso.

Next thing that we do is what we call “body size normalization”. Basically all the body lengths, such as the distance between the elbo and hand, are scaled up or down to a standard body size. This ensures that the variation in bosy sizes is captured at the feature level itself, and our model does not have to worry about it anymore.

Clicke here to get the MATLAB code that does the feature extraction part from skeleton files that were obtained from the MSR dataset.

Model

Now, as I discussed in my previous post, Hidden Conditional Random Fields (HCRFs) was the model that we finally selected. The original authors had released a well documented toolbox, to which we directly fed the features that were computed above.

Results

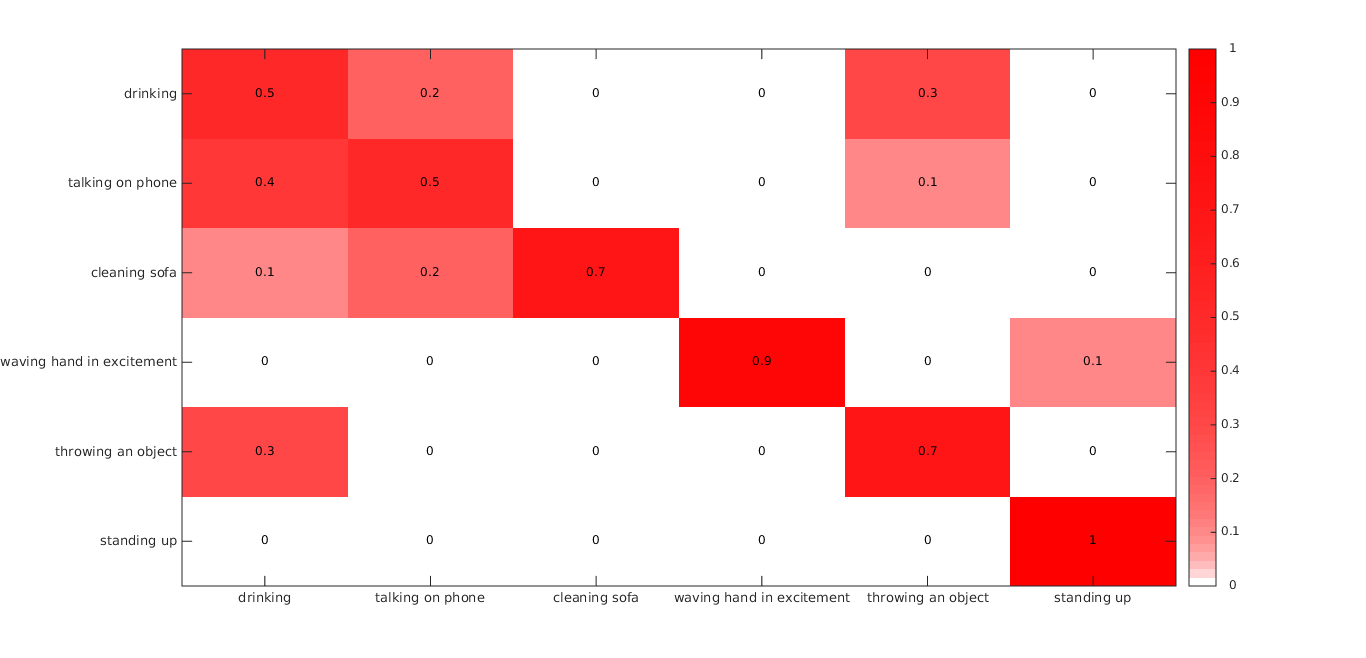

Five-fold cross-validation without any hyper-parameter tuning yielded a precision of 71%. These results do not seem impressive on first glance, but it must be noted that all our experiments were performed in the “new person” setting i.e. the person in the test set did not appear in the training set, and we did not do any hyper parameter tuning. Our results can be summarised in the ollowing heatmap:

The above figure made one thing clear: that accuracy is being seriously harmed by the algorithm’s inability to correctly distinguish between drinking and talking on phone. The reason for this is relatively simple. The features that we are using are skeletal features, and therefore we do not pay any attention to what objects the human is interacting with. If you look at the skelat stream, talking on the phone, and drinking water seem extrmemly similar! In both the cases, the human raises a hand, and brings it near his head. Thus, in order to make a truly useful activity detection system, it is important to model these interactions explicitly.

If we do get around to improving this model, I will post it here.